Last week, we sort of opened a can of worms when we began a (really brief) discussion on helmets, universal helmet laws, and why the United States CDC would worry about motorcycle riders and whether or not they choose to wear a helmet.

There are a LOT of opinions about helmets, and nearly as many studies about them, too, the truth of the matter is this:

The decision to wear a helmet, and the style of the helmet, and the certifying body that states your helmet is safe to wear is an intensely personal decision.

We promote more than one kind of helmet for those reasons!

When it comes down to it, though, what are the various certifying organizations and what do the certifications actually mean? There’s a lot of misinformation online and in print, so we thought we’d try to get some of the facts in this post to help you understand what that alphabet soup of numbers and letters on the back of your helmet really means.

DOT, Snell, and ECE…

Effectively, there are three primary certifications in the world of motorcycle helmets, and those are the United States’ DOT. Snell is a non-profit operating in North America, and the ECE is the largest recognized standard, found in nearly 50 countries and used by most racing organizations. The U. K. has one, too – the SHARP, and Australia uses the CRASH, but these represent smaller bodies in the conversation.

Which one is “best?” That’s pretty subjective, but we’ll get into the various testing mediums in a few moments. At The Bikers’ Den, we’ve found the most common of all of them – due to operating in North America, is the DOT standard. Let’s start there…

DOT Standard

Most folks who like any other certification standard will tell you how bad the DOT standard is, but the reality is, it establishes a baseline for helmet safety.

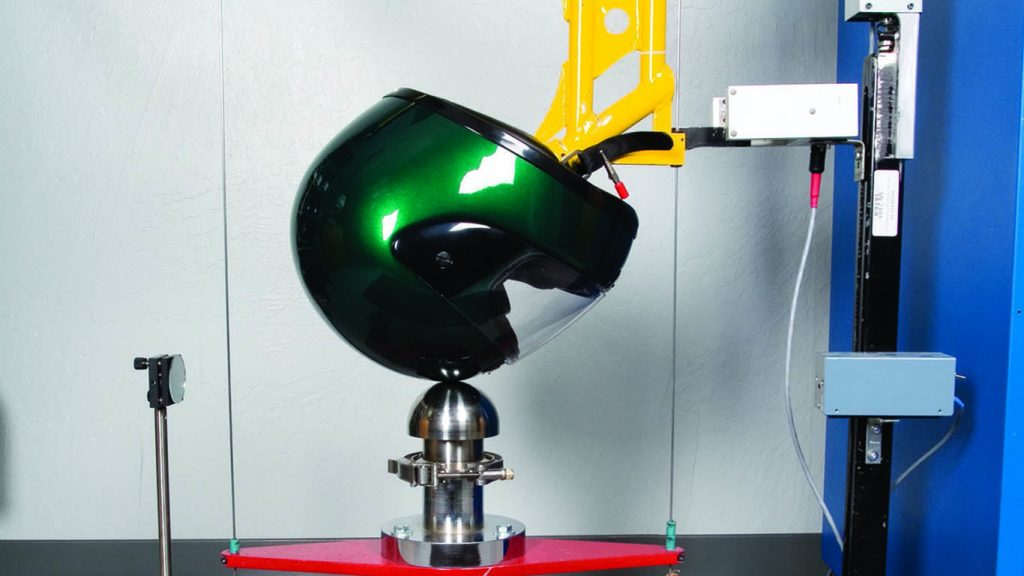

In essence, a series of sensors shaped like a head is placed in the helmet and dropped from certain known heights, the G-forces are measured, and the helmet either passes of fails. In reality, it’s a lot like falling off a bike. Other tests include the helmets ability to withstand certain stresses for a length of time as well as a certain amount of weight being applied with a pointed anvil. Where people get mad is that the manufacturer is the one responsible for the testing, and they are the ones that do the actual certifying of the helmet design.

You guessed it – that’s where everyone begins to assume the manufacturer is simply slapping the sticker on it and saying it’s safe. While we’d admit that could happen, since the DOT is known to test helmets, if the helmet actually doesn’t pass when tested by them, they can assess a fine up to $5,000 per helmet.

That is a powerful incentive to build it right.

Snell

The Snell Memorial Foundation is a non-profit American organization that is often portrayed as superior to the DOT standard. While there is no arguing that Snell is more in-depth, since every one of the tests by any certifying body are done in labs, it’s always been hard to argue what is “better.”

Snell devises a new certification every five years, and while the 2020 standard is now out, detractors of Snell say that their reliance on G-force testing resulted in an “overbuild” of the helmet. In Snell, different areas of the helmet are tested, and even the visor (if so equipped, is tested, too).

There is no denying that Snell impact standards have been set higher, but we’ve noticed in the last two certifications, those have become more aligned with DOT and ECE standards.

Right or wrong, Snell certification still gives you data to work with.

ECE

The ECE (Economic Commission for Europe) standard on paper seems to be a fair balance for helmet testing, although it is usually not acknowledged in North America except in racing.

There are many similarities to the other testing bodies, with a few notable differences. For starters, the visor is tested as a part of the helmet. Additionally, the chin strap is tested in two ways – one, the relative strength of the strap and the buckle itself for slippage – and the helmet shell is tested for abrasion – as though you were skidding along the pavement after dumping the bike.

One thing that marks a notable difference is that, unlike the DOT “honor system” or the Snell “optional” testing, the ECE tests every helmet design before it can be sold. Of course, this is Europe, so they have to make that test strange: a third party actually handles the testing, with officials from both sides in attendance.

So Who’s Right?

That’s the $64,000 question, isn’t it? The truth is, in our research for this post, we found not one single incident of a motorcycle crash happening in a lab.

They happen on the streets, with a wide range of variables – the physical condition of the rider being a prime one. The simple fact is a woman who weighs 120 pounds doesn’t retain the kinetic energy in a slide that a 300 pound man does, and does that rider hit pavement, a curb, a patch of dirt, or an oncoming car?

There’s no simple way to accommodate all the variables involved in a crash, so, at least to us, having the helmet you feel the safest about and that represents the best one you can afford is still the best choice.

…And yes, that includes the style of the helmet. The smallest beanie on the market is going to protect your head and neck differently than a full helmet with a visor and chinbar. Note: we said differently, not “better” or “worse.” If the increased visibility you get with a beanie means you avoid being blindsided, so you avoid the accident altogether, did your helmet “save” your life?

We’d say yes.

Helmets help, but it’s not always because of the sticker on the back of them.